Stay Connected with eSIMs in Japan

Get mobile data in Japan in minutes. Ballpark pricing in yen, compatible iPhones, Galaxies and Pixels, quick setup steps, and how to unlock your iPhone if needed.

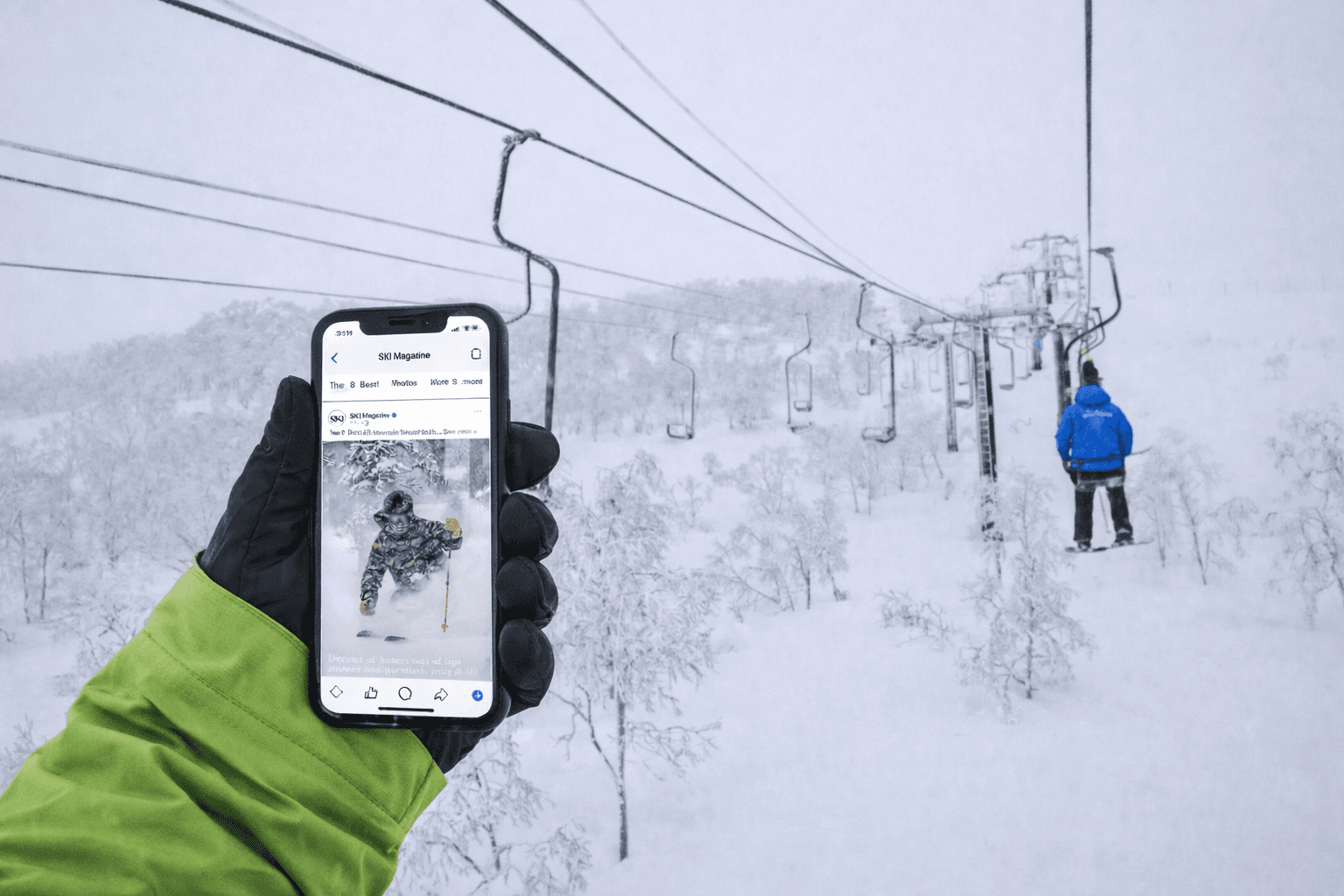

Japan’s backcountry and sidecountry are a big part of the Japow fantasy: deep tree lines, long untracked pitches, skin tracks through quiet birch forests, iconic peaks like Yotei in the background.

They’re also where people get hurt and killed.

This guide is here to help you understand what “backcountry” and “sidecountry” mean in Japan, how gate systems and ropes actually work, and what a safe day beyond the resort looks like in broad strokes. It is not avalanche training and it is not a how-to manual for rescue. If you take one thing away, make it this:

Reading a guide on the internet is not enough to keep you safe in avalanche terrain. You still need proper education, practice, and – for most visitors – a qualified local guide.

With that in mind, let’s talk about how to chase Japow beyond the ropes without pretending that “it’ll be fine” is a plan.

Different countries use these words differently, and that confusion alone can be dangerous.

Off-piste (in this guide) means riding inside the resort boundary but off the groomed runs. Think trees between marked pistes, powder pockets under a chair, or cut lines that are still within the patrolled area. Resorts differ: some welcome it, some tolerate it, some ban it outright. You need to know which is which.

Sidecountry in Japan usually means terrain that’s outside the resort boundary but accessed from a lift, often via marked gates. Niseko is the classic example: you ride a lift, exit through an official gate, and you’re in uncontrolled, unpatrolled terrain. It may look like “just another run off the top”, but once you step through that gate you are, for all practical purposes, in the backcountry.

Backcountry here means anything that’s fully outside the resort system: touring days, sled drops, big objectives, longer traverses and so on. You’re earning your turns by skinning or bootpacking, and you’re fully responsible for route choice, navigation, weather and avalanche risk.

One of the biggest mindset shifts for visitors is accepting that “through a gate under a lift” does not mean “safe like a piste”. In places like Niseko, local rules make this explicit: use gates, never duck ropes, respect closures, and remember there’s no safety control or patrol beyond the boundary.

If you’re not ready for that level of responsibility, you’re not ready for sidecountry or backcountry yet – and that’s totally fine.

Japan’s snow is famously deep, but depth doesn’t mean safety.

Most of Japan’s major snow regions have a maritime to continental-maritime snowpack: big, frequent storms; wind-loading; temperature swings; and the kind of terrain where avalanches can run through trees, onto traverses, or into gullies that feel “pretty low angle” until something breaks above you.

Risks that often surprise visitors include:

On top of that, there’s the human factor: following strangers’ tracks, pushing past closures because “locals are doing it”, or treating gates as permission instead of a reminder that you’re leaving the controlled environment of the resort.

Japan has a growing avalanche safety culture—organisations like the Japan Avalanche Network (JAN) publish regional bulletins and training resources—but those bulletins are only useful if you actually read, understand and act on them.

Bottom line: snow that looks friendly and playful in photos can still kill you if you misread it.

This is the uncomfortable question, and it’s the most important one.

If you’re on your first Japan trip, have no avalanche training and are mainly used to resort skiing or boarding, you’ll get more than enough joy from inbounds pow and mellow trees. Japan has loads of resorts where you can ride deep snow on marked or patrolled terrain and still feel like you’ve “done” Japow.

If you’re a strong off-piste skier or rider with some avalanche education but limited experience in Japan, the safest way to step into sidecountry or backcountry is to hire a local guide or join a reputable guided group. You’ll learn the local gate system, how to read bulletins, and what “normal” looks like in that region’s snowpack, all while someone experienced makes the big calls.

If you’re an experienced backcountry crew with solid avalanche training, regular practice and a history of conservative decision-making at home, Japan is still different. You’ll need time to learn how local weather, snow and terrain interact, how gate policies work, and where to find reliable information. It’s smart to start with guided or low-consequence days before you start drawing your own bigger lines.

The consistent theme: if in doubt, upgrade your education, your guiding, or your terrain choices before you upgrade your risk.

Many of Japan’s most famous powder resorts have some version of a gate system. The best-known is Niseko’s: a series of numbered backcountry gates that patrol open or close based on weather, avalanche risk and other factors. The Niseko Rules spell out the basics clearly: always use the gates to leave the resort, never duck boundary ropes, do not enter off-limits areas, and stay inbounds when gates are closed.

Other areas have similar concepts, even if they’re less formalised. You’ll see:

It’s tempting to think “it’s only a short dip under that rope”, especially when you can see people doing it. That mindset is exactly what local patrols are fighting. Ropes are there because someone who understands the terrain decided that whatever is on the other side is currently not safe or not manageable for the patrol and rescue system.

If you want to ride sidecountry, the bare minimum is:

If that feels restrictive, remember that the gate system exists to enable safe sidecountry access as often as possible, not to shut it down. Patrol in places like Niseko work hard to open gates whenever conditions allow; respecting closures is how you support that.

For any tour or gate-accessed sidecountry day, you should be asking three basic questions before you even think about dropping in:

In Japan, key starting points include:

Bulletins are not guarantees. They’re expert-informed snapshots that help you understand what kind of avalanche problems are on the menu and where they’re most likely to matter. It’s still up to you (or your guide) to choose terrain that fits the conditions and your group’s skills.

If you’re not confident reading and applying bulletins, that’s a clear sign that you should either stay inbounds or go with a qualified guide and learn.

Any time you’re exposing yourself to avalanche terrain – which absolutely includes many sidecountry runs – a few things are non-negotiable.

Every rider in the group should have the core avalanche kit: a modern transceiver (beacon), a proper metal-bladed shovel and a probe, plus the knowledge and practice to use them under stress. Avalanche organisations and training providers around the world are very consistent on this point.

Add to that:

This guide intentionally does not walk you through how to do a beacon search or a group rescue. That’s something you need to learn from certified instructors and practise regularly in person. Written steps are not an adequate substitute.

Think of this section as your gear literacy checklist: if you don’t recognise these items or you’ve never practised with them, you’re not ready for self-guided backcountry days in Japan yet.

A lot of the social media hype around Japan’s backcountry is about zones, not systems: “this ridge”, “that bowl”, “those trees”, “that peak”.

For long-term safety, what matters far more is:

That’s exactly what avalanche courses and guided days are designed to build.

Avalanche education providers (in Japan and overseas) offer structured courses that cover recognition of avalanche terrain, basic snowpack understanding, use of gear and decision-making frameworks. Many Japanese regions also have local seminars and workshops linked to JAN’s education work.

When you combine that with time spent in the field with a qualified local guide, you get the best of both worlds: general avalanche skills plus specific knowledge about how Japanese snow and terrain behave.

If you’re going to spend money anywhere in your backcountry journey, this is where it has the biggest safety return.

It’s uncomfortable to think about worst-case scenarios, but that discomfort doesn’t make them less real.

A few practical points:

A simple rule of thumb: if you’d be uncomfortable explaining your choices to patrol or a rescue team after the fact, it’s probably not a good choice in the first place.

A good day beyond the ropes in Japan doesn’t just end without incident. It feels boringly well-managed along the way.

You start with a clear plan and a sense of the day’s hazard. You or your guide adjust that plan if the weather, snow or visibility isn’t playing ball. The terrain you actually ride bumps up against your comfort level every now and then but never blows past it.

In a well-run group, you don’t all drop onto the same steep slope at once. You regroup in safe spots, keep eyes on each other, and stay vocal about how things feel. Nobody is bullied into lines they don’t want to ski or ride. When something doesn’t look right – a wind-loaded convexity, a gully that feels like a terrain trap, roller-balling on a warm aspect – you back off and choose something mellower.

At the end of the day, you should be able to point not just to the “best powder run”, but to at least one moment where your group deliberately turned away from a tempting line because conditions or gut feeling said no. That’s what a mature backcountry culture looks like.

It can be, if you combine conservative terrain choices, current avalanche information, proper gear, real training and – for most visitors – local guiding. It becomes unsafe quickly when people treat gate access as a green light to ignore closures, follow random tracks, or ski avalanche terrain without the skills to manage it.

Not automatically. The only thing the gate guarantees is that patrol believed, at that moment, that letting people out there with their own gear and judgment was acceptable. Once you pass the gate, you’re in uncontrolled terrain. That may or may not be safer than a low-angle tour you’ve planned yourself in a different region.

Yes. A guide is not a force field. Reputable operators will either require you to bring or rent appropriate gear (transceiver, shovel, probe at minimum) and will expect you to wear and carry it properly. Safety is a group responsibility, not something you outsource to the person at the front.

Tracks tell you where someone went, not whether they understood the hazard, made good decisions, or just got lucky. Following strangers into consequential terrain is one of the most common human-factor traps in ski touring and sidecountry. Treat other people’s tracks as information, not permission.

Being a strong skier or rider is essential, but it’s only half the equation. You also need mountain judgment, avalanche knowledge, local familiarity and the ability to say no when it matters. If you’re missing any of those, start with guided days and moderate objectives while you build the rest.

Backcountry and sidecountry in Japan are incredible. They’re also unforgiving when you get them wrong. If you respect local rules, learn how the snowpack works, carry the right gear, invest in real training, and lean on good guiding while you learn, you’ll not only unlock more of Japan’s terrain — you’ll also stack the odds heavily in your favour of coming home with nothing worse than tired legs and a full camera roll.